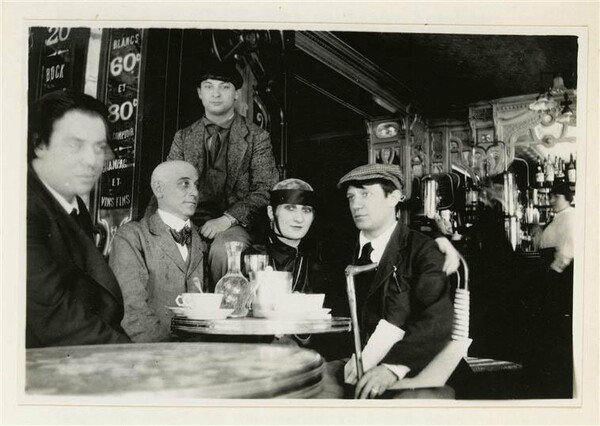

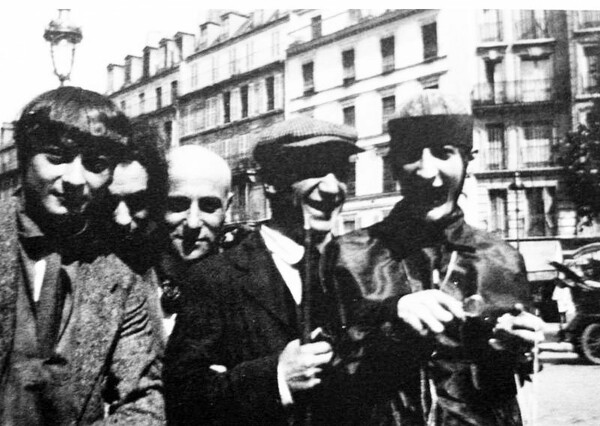

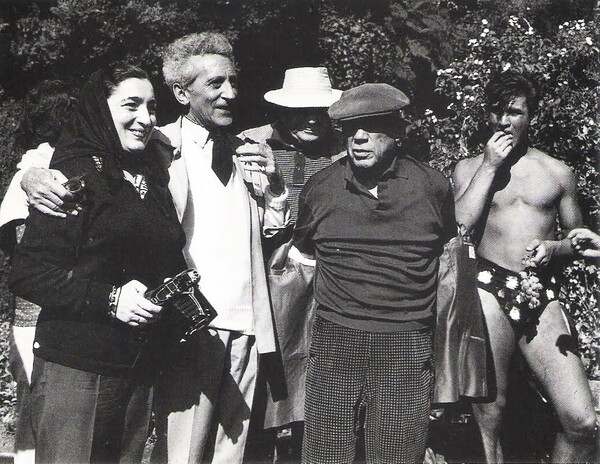

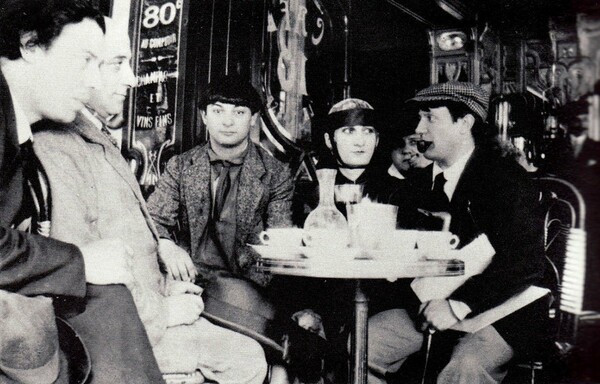

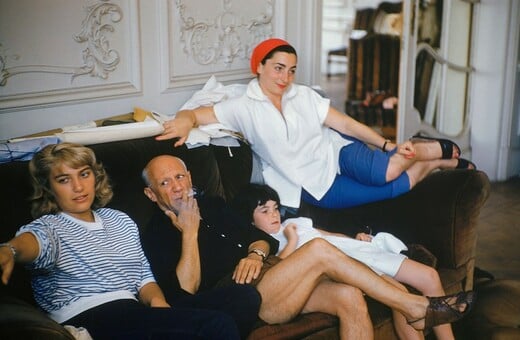

Café de la Rotonde (Montparnasse). Από αριστ., ο χιλιανός ζωγράφος Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, ο συγγραφέας Max Jacob, ο ζωγράφος Moïse Kisling, το μοντέλο Pâquerette (Emilienne Geslot) και ο Pablo Picasso. Βλ. ineedartandcoffee.blogspot.com.

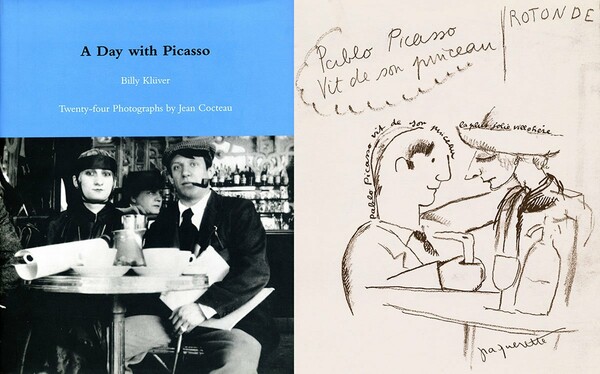

Για την ιστορία των φωτογραφιών (24 συνολικά), βλ. πιο κάτω το πρώτο κεφάλαιο (στα αγγλικά δυστυχώς) του βιβλίου του Billy Kluver "A Day with Picasso". Για τις φωτ., βλ. flickr.com και cocteau.biu-montpellier.fr.

Πάνω στο σχεδιό του, ο Jean Cocteau σημείωσε : "Ο Pablo Picasso ζει από το πινέλο του" και "η Pâquerette, η πιο όμορφη έκφυλη".

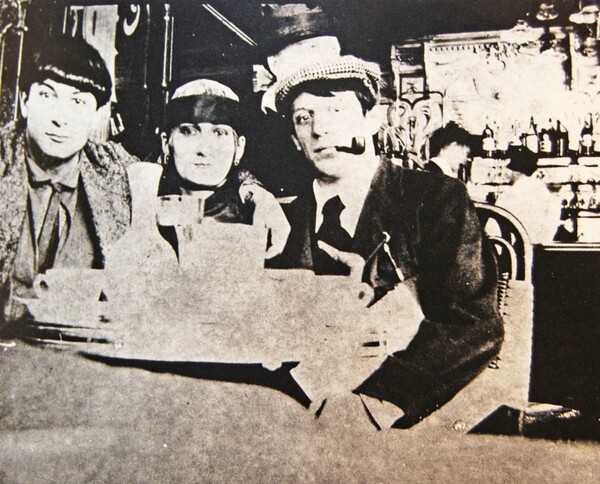

Στη φωτογραφία του εξωφύλλου, ανάμεσα στην Pâquerette και τον Pablo Picasso διακρίνεται η ρωσίδα ζωγράφος Marie Vassilieff.

Βλ. sfgate.com.

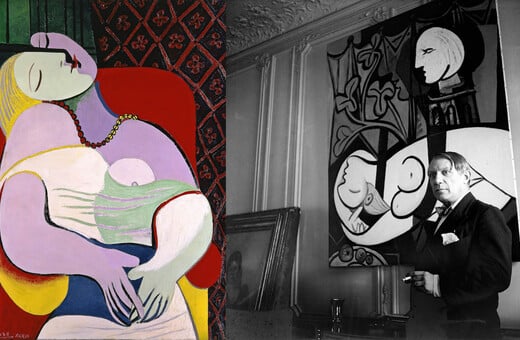

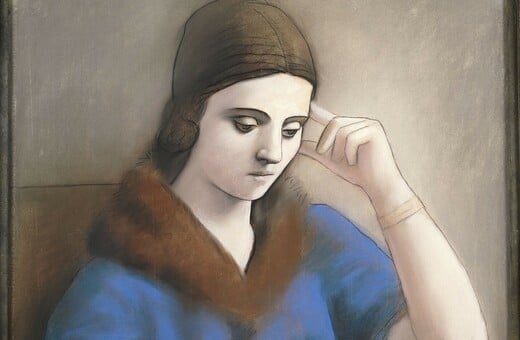

Βλ. Réunion des musées nationaux.

Βλ. Wikimedia Commons.

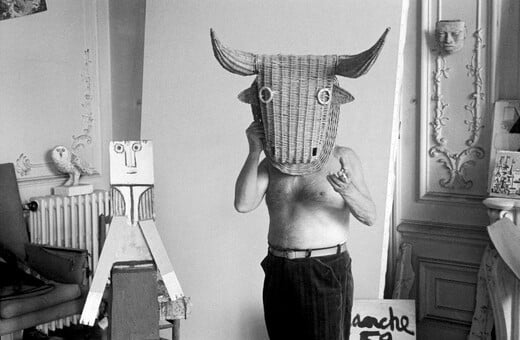

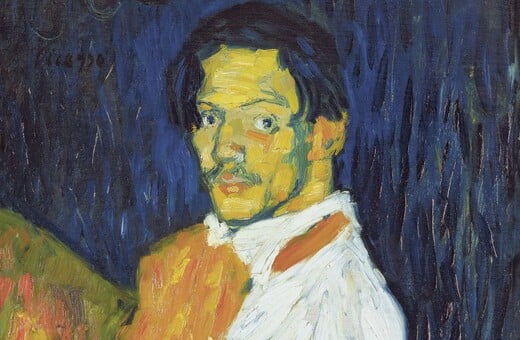

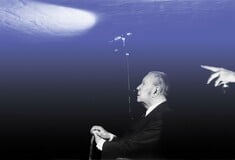

Ο Pablo Picasso. Βλ. sfgate.com.

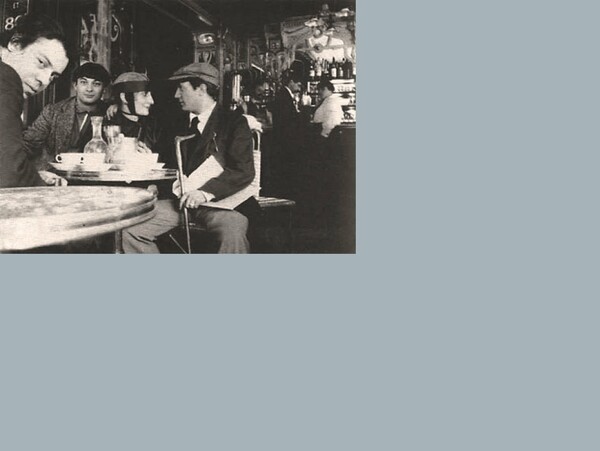

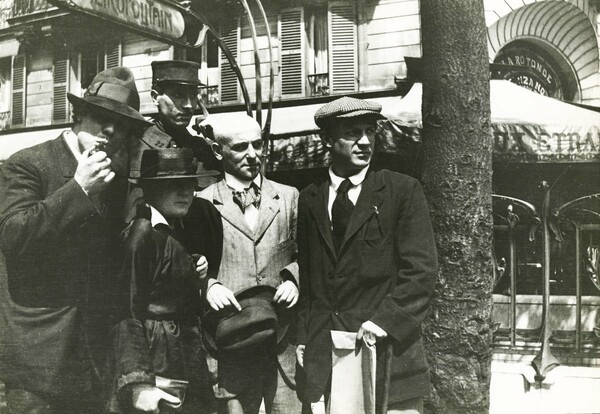

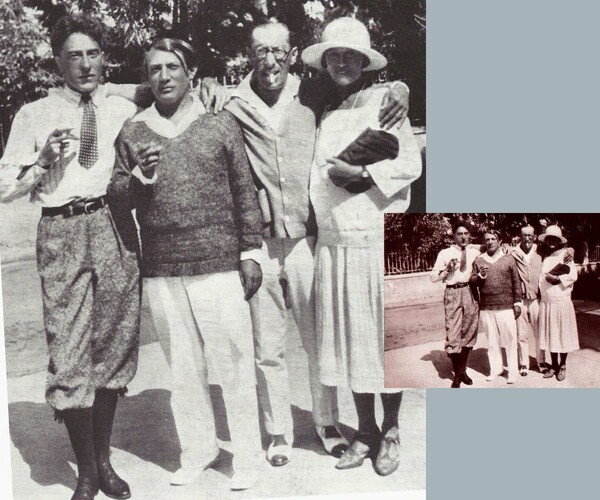

Από αριστ., ο Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, ο Henri-Pierre Roché με τη στολή (συγγραφέας του αυτοβιογραφικού μυθιστορήματος Jules et Jim), η ζωγράφος Marie Vassilieff, o Max Jacob και ο Pablo Picasso. Βλ. Réunion des musées nationaux.

Βλ. fantomas-en-cavaletumblr.

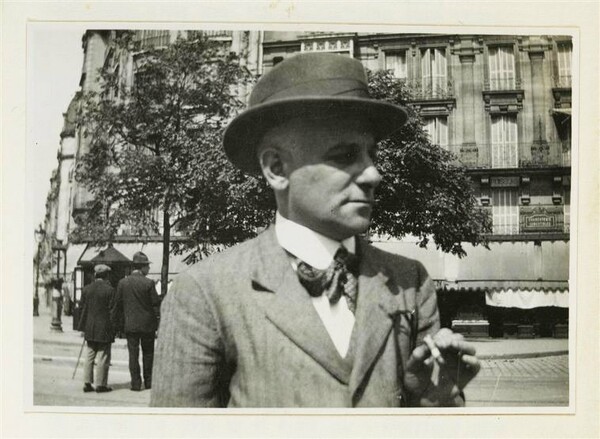

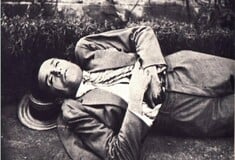

Ο Max Jacob. Συνελήφθη το 1944 από την Γκεστάπο λόγω της εβραικής του καταγωγής και πέθανε στο στρατόπεδο του Drancy από εξάντληση μέσα σε δύο εβδομάδες. Βλ. angeheurtebisetumblr.

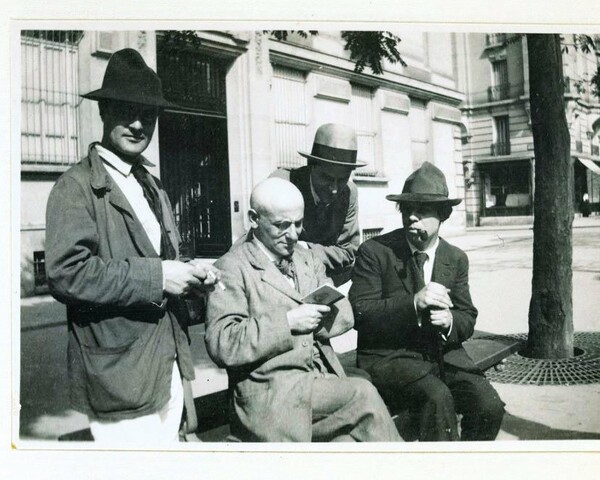

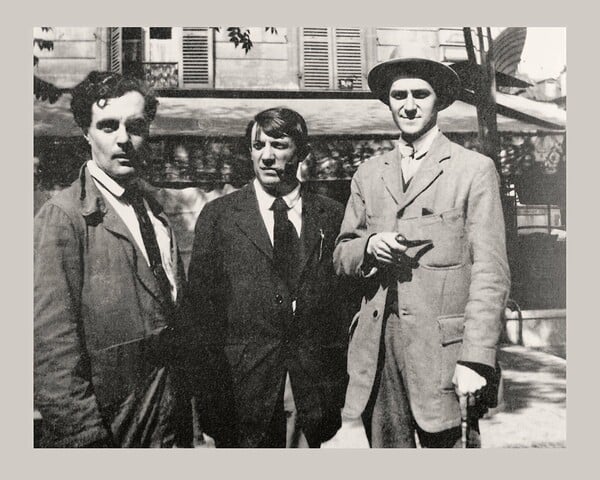

'Ενας ακόμη στην παρέα, ο Amedeo Modigliani (αριστερά). Μαζί του, μπροστά στο ταχυδρομείο του boulevard de Montparnasse, ο Max Jacob, ο συγγραφέας André Salmon και ο Manuel Ortiz de Zárate. Βλ. Corriere Viaggi.

Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, επιστήθιοι φίλοι από το 1901. Ο Picasso ήταν και ο νονός του Max Jacob, όταν ο τελευταίος αποφάσισε να βαπτιστεί ως Χριστιανός όταν είδε τον Χριστό να εμφανίζεται στον τοίχο του δωματίου του. Βλ. picstopin.com και The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Από αριστ., ο Moise Kisling, ο Ortiz de Zarate, ο Max Jacob, ο Pablo Picasso και η Pâquerette. Βλ. matthewedwardstumblr.

Ο Moise Kisling και ο Pablo Picasso με το καρότσι του μανάβη. Βλ. cocteau.biu-montpellier.fr.

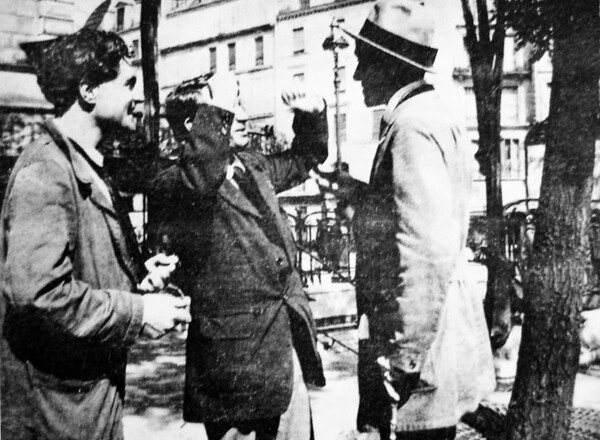

Ο Amedeo Modigliani, ο Pablo Picasso (που χειρονομεί) και ο André Salmon . Βλ. Wikimedia Commons.

Οι ίδιοι. Βλ. simonamaggiorelli.com.

Ο Jean Cocteau με τον Pablo Picasso μερικές δεκαετίες μετά. Βλ. theredlist.fr.

Ο Jean Cocteau, ο Pablo Picasso, ο Igor Stravinsky και η χορεύτρια Olga Khokhlova (πρώτη γυναίκα του Pablo Picassio) στη Νότια Γαλλία (Antibes, 1926). Βλ. loscoloresdelamusica.wordpress.com.

Ο Jean Cocteau με τον Pablo Picasso στο Μονακό. Βλ. Monaco Hebdo.

By BILLY KLUVER

The MIT Press

In 1978 I began to collect documentary photographs of the artists' community in Montparnasse in the first decades of this century for a research project which in 1989 resulted in the publication of Kiki's Paris. Most of them were amateur photographs by unknown photographers, and I became aware that some previously unassociated photographs from different sources fell into groups that appeared to have been taken on the same day. The largest of such groups consisted of five of the photographs presented here. Over the next few years, I found five more published photographs that belonged to this group. The indications that these photographs belonged together were that the same people appeared in the photographs, wearing the same clothes in each shot and with the same accessories-pipes, hats, and canes. Their ties were knotted the same way and their collars had the same wrinkles in them.

When I came across the tenth photograph (No. 24 in the sequence in which they were taken) reproduced in the catalogue of the Modigliani exhibition at the Musee d'art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in spring of 1981, with its very distinct shadows on the buildings in the background, it occurred to me that if the building could be identified, it might be possible to use these shadows to determine the exact day and time the photographs were taken.

First, I examined the photographs for other internal clues to where and when they were taken. On some of the photographs the awning of the Cafe de la Rotonde could be seen in the background. The foliage on the trees and the clothes people were wearing suggested that the time of year was late spring or summer. The deserted streets and the presence of a man in uniform suggested the years of World War I.

Next I established the whereabouts of three of the most easily identified people in the group, Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and Moise Kisling. Modigliani was in Nice from March 1918 to May 1919. Picasso spent the first years of the war in Paris; but on February 17, 1917, he went to Rome with Cocteau to work on the ballet Parade, where they stayed until the beginning of May. A few weeks after the performance of Parade on May 18, Picasso followed his new love, the ballerina Olga Khoklova, to Spain and stayed there until November. Kisling joined the Foreign Legion in the first days of the war and was wounded in May 1915. During the rest of 1915 he was recuperating in Brittany. He made a trip to Spain in March 1916, but was back in Paris in late April of that year. Thus, I was able to rule out the years 1915, 1917, and 1918. Since both Kisling and Picasso were out of Paris when war was declared at the beginning of August 1914, I concluded that 1916 was the one year when all three were in Paris during the summer.

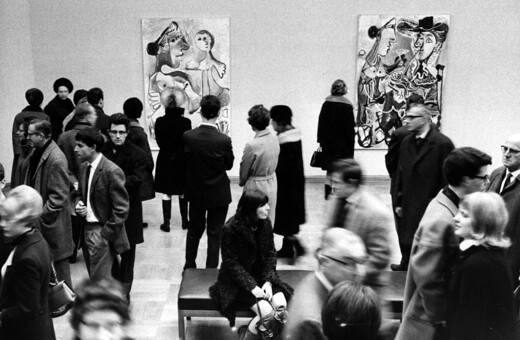

Was there an event in the late spring or summer of 1916 that would have brought all the people in the photographs together, which would lead to a date the photographs were taken? From the chronology in the catalogue of the museum-wide Picasso retrospective held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from May to September 1980, I learned that Picasso showed Les Demoiselles d'Avignon at an exhibition called Salon d'Antin in duly 1916, and that this exhibition had been organized by Andre Salmon.

Edward Fry owned a copy of the Salon d'Antin catalogue and sent me a photocopy, which revealed that all the artists in the photographs were included in the exhibition. I proceeded on the assumption that their meeting in Montparnasse could have been connected with activities surrounding this exhibition-the opening or closing, whose dates were not given in the catalogue, the musical performances on July 18 and 25, or the poetry readings on July 21 and 28. This assumption focused my attention on late July 1916.

I then set out to determine whether the measurements of the angles and lengths of shadows in the photographs could yield a closer date. I had already identified the buildings in the background, all of which were located on Boulevard du Montparnasse and were the same in the 1980s as they had been in 1916. Such identification was made easier by the distinctive grillwork in front of the windows. For buildings constructed after the turn of the century, architects took pride in ordering grillwork to be specially fabricated with different patterns for each building. Using maps of the area in the scale of 1:500, published by the city of Paris, I established where each photograph was taken. I then took photographs and made measurements on the buildings, an undertaking that was made difficult by some unfriendly tenants who would not allow their ledges or window insets to be measured. On the basis of the measurements I was able to make, I calculated the sun's positions and plotted the results on a standard chart which related the sun's positions to the time of day and day of the year for Paris. The plotted points gave me a spread of three weeks, with the most probable date being August 12.

Discouraged by the uncertainty in this process, in 1983 I approached Liliane Bergeal and Patrick Rocher at the Bureau des Longitudes and asked them if it were possible to achieve a more accurate date from the photographs. Working on one shadow on one photograph, they also found that it was not possible to determine the date closer than within 20 or 30 days but that August 12 did fall within that period.

The identity of the photographer and of all the people in the photographs was established in the following way. I had easily identified Picasso, Modigliani, and Kisling. Four of the photographs had been published in the Parisian magazines Paris-Montparnasse and Bravo in the late 1920s; and there I had found identifications of Andre Salmon, Manuel Ortiz de Zarate, and Max Jacob, and a reference to the woman in photographs 8-11 and 13-15 as "Mile. P . . . ". I still was not able to identify the woman in photographs 5, 8, and 9 or the man in the uniform, nor did I know who "Mlle. P . . . " was.

Andre Bay, an editor at Editions Stock, gave me a book of drawings by Jean Cocteau that he had found when cleaning out his office. In it were two drawings that had an uncanny resemblance to the photographs, and Cocteau had inserted himself into one of them. Also, the woman I knew only as Mlle. P . . . was identified as Paquerette, a model for the designer Paul Poiret.

On my next trip to Paris, in July 1982, I asked Anne de Margerie for someone who could confirm that Cocteau was the photographer. She suggested Pierre Chanel, who was the director of the Musee de Luneville and author of Album Cocteau. I called him; and he said, "Of course the photographs were taken by Cocteau." The next day I took the train to Luneville. Chanel had catalogued six additional related photographs in the Cocteau archive; together we had sixteen photographs.

Chanel was able to identify the remaining two people in the photographs. I asked him to describe how he had discovered their identities.

He wrote:

- When I classified the archives of Jean Cocteau at Milly-la-Foret after his death in 1963, I found the negatives of most of the photographs taken by Cocteau in Montparnasse. I published one in Album Cocteau, which I was preparing at the time. I dated the photographs to 1916 based on Cocteau's preface in his book on Modigliani.

In this book Cocteau had written:

In 1916 during the war, it was Montparnasse. I was there through the mediation of Picasso. His windows overlooked the graves of the Montparnasse cemetery.... We went out and visited studios of the cubists. Our promenade took us to the Cafe de la Rotonde. The Rotonde, the Dome, and a restaurant at the corner of boulevards Raspail and Montparnasse formed a town square, where the vegetable sellers stopped their small carts and grass grew between the paving stones.... Nothing documents this except some photographs I took one morning at the Rotonde.

Chanel continued:

What remained was to identify the people in the photographs. Kisling, Modigliani, Picasso, Andre Salmon and Max Jacob were easy to recognize. As for the four others: it was Valentine [Gross] Hugo and Andre Salmon--both of them at the end of their lives--who identified them for me. I presented my group of prints to Valentine Hugo, now 80 years old, in a visit to her apartment in Paris on January 21,1968. She positively recognized the military person who intrigued me, Henri-Pierre Roche.On vacation in the south in August 1968, I presented the prints to Andre Salmon at his villa at Sanary-sur-Mer. He easily identified Manuel Ortiz de Zarate, Marie Wassilieff and Paquerette. Salmon recalled that Ortiz was a lover of hashish and that Paquerette, the model for Paul Poiret, had soon after this married a doctor, Raymond Barrieu, who was posted to North Africa.

I later found that Henri-Pierre Roche had been identified by Roland Penrose when he published photograph No. 4 in his biography of Picasso, but he had dated the photograph to 1915. The photographs had frequently been misdated and the people misidentified. Among the most amusing misidentifications was the one of photograph No. 5 in which Roche and Wassilieff were identified as M. and Mme. Henri Laurens. Henri Laurens had a wooden leg and never served in the army. Another catalogue reproduced photographs Nos. 4 and 16 and credited Man Ray, who arrived in Paris in 1921, the year after Modigliani died.

Anne de Margerie was working with the Cocteau archives and Edouard Dermit, Cocteau's longtime friend and executor of his estate, to prepare a Cocteau exhibition for the Grey Gallery at New York University in 1984. She located the negatives and original contact prints for fourteen of the photographs that Pierre Chanel had catalogued. An additional two photographs existed only in reproduction in the magazines Paris-Montparnasse and Bravo and two others were in private collections in France, making eighteen photographs in all.

The date was fixed when Anne de Margerie, who was also working on a book on the artist Valentine Gross, found a letter Cocteau had written to Gross on August 13, in which he stated, Picasso takes me to the Rotonde," and went on to comment on his visit. Francis Steegmuller had included this letter in his 1970 biography of Cocteau, but had left out the one sentence that I needed: "I made films with Picasso and Mlle. Paquerette... Cocteau's letter pointed strongly to August 12 as the date, and I had the idea that this could be confirmed if Henri-Pierre Roche had mentioned something about the lunch in the extraordinary diary he kept for more than fifty years. Carlton Lake provided me with the entry for August 12, which established that Roche had indeed met Picasso and Cocteau for lunch that day.

I then ordered meteorological reports from the Bureau Central Meteorologique that confirmed that August 12, 1916, was sunny all day, except for a few scattered cirrus clouds, with a high-pressure area centered over Paris.

With the date established, Bergeal and Rocher gave me a computer printout of sun positions for August 12, 1916, for the longitude and latitude of the Observatoire de Paris on Rue Denfert-Rochereau in Montparnasse, less than a kilometer from the Rotonde. I used this information to calculate the time of day the photographs were taken, which is a simpler and more accurate procedure than determining the date from shadows on the photographs. To calculate the time of day, I used the angle of the shadow that the sun's rays make on a vertical plane from a vertical or horizontal obstruction. The accuracy of the timing varies from photograph to photograph. In some cases, the sequence had to be established by other internal clues, such as the change in the length of shadows and the change in position of the people.

With the time and sequence established, and on the basis of other information I had gathered, I constructed a scenario of the events of the four hours during which the photographs were taken. I published my findings on the eighteen photographs in an article, "A Day with Picasso," in the September 1986 issue of Art in America.

In 1989, Pierre Chanel found another photograph, No. 18 in the sequence, at the Cocteau archives; and in 1992 Helene Seckel, curator at Musee Picasso, found a twentieth photograph, No. 23 in the sequence, in the Archives Picasso. In May 1993, Andre Cariou, conservateur at the Musee des Beaux-Arts de Quimper, wrote me that he had found a twenty-first photograph, No.6 in the sequence, in the archives of his museum. That year a young German curator, Udo Kittelmann, proposed to make a book from the original article, and Ein Tag mit Picasso was published by Cantz Verlag with twenty-one photographs. A French edition, Un jour avec Picasso, was published the next year by Editions Hazan. In February 1994, research curator Judith Cousins at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, discovered an original contact print of photograph No. 9 in the series in the Alfred Barr Papers at the museum. In March 1996 Helene Seckel found a twenty-second photo, No. 17 in the series, and a contact print of photograph No. 11, in a copy of Cocteau's manuscript for a 1917 poem, Ode a Picasso, which he had given to Picasso.

Cocteau carefully preserved at least eighteen contact prints or negatives of the photographs; but he distributed prints soon after the photographs were taken. Duplicates or contact prints of the missing photographs have been found in the archives and papers of the people in the photographs (Picasso, Jacob, Roche, Gross, and Satie), or of people who were connected with members of the group.

In Ein Tag mit Picasso, I published one of two photographs Cocteau had taken of Erik Satie and Valentine Gross on the balcony of his mother's apartment at 10 Rue d'Anjou, now No. 2 in the series. I suggested that Cocteau had taken it before August 12, but on the same roll as the photographs he took in Montparnasse. Valentine Gross was in Paris when Cocteau returned from the front on July 28, and he wrote her continuously during this time. A letter from Satie to Gross, who was a friend and admirer of the composer, established that Cocteau and Satie worked together on Parade on August 9, possibly for the first time since Cocteau's return from the front. A letter dated August 9, in which Cocteau reports to Gross, "very good day's work with Satie," makes it unlikely that Gross was at Cocteau's apartment that day. The photographs were taken too late in the morning for Cocteau to have had time to take them on Saturday the 12th, before he met Picasso for lunch in Montparnasse. On August 13 Cocteau was writing Gross in Boulogne-surMer, where she had gone on one of her frequent trips to visit her mother. In a letter from Gross to Cocteau on August 15 from Boulogne, she wrote, "Have you printed your photo? I want to see it quickly. Photo Satie and I, the prints, quickly," Thus, the photograph of Gross and Satie must have been taken before she left for Boulogne, that is, before August 12. Then the photographs of her and Satie at 10 Rue d'Anjou are most likely to have been taken on August 10 or 11. I have been unable to narrow it down any further.

When I saw a reproduction of the second photograph of Satie and Gross, in Andre Fraigneau, Cocteau par lui-meme, I realized I could use the shadow on the wall behind them to time the photograph. I contacted Pierre Chanel, who as it turned out had the negatives for both photographs. They are printed here together for the first time. During a trip to Paris in September 1996, I was able to go to 10 Rue d'Anjou, which had most recently been the headquarters of Banque Colbert but was now empty, the bank having gone out of business. A helpful gardien took me up to the fourth floor and out onto the balcony that surrounds the courtyard, where I located where Satie and Gross had stood and took photographs of the architectural features that appear behind them in Cocteau's photographs.

The twenty-four photographs presented here--four rolls of film of six photographs each--are all of the photographs that Cocteau took between August 10 and August 12. While I have seen many photographs that Cocteau took while he was serving at the front, I have found no other groups of photographs by him until those taken in Rome between February and early April 1917, where he went with Picasso to work on Parade for Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.

Throughout his life Cocteau never hesitated to work in different art forms: poetry, novels, theater, dance, film, and painting. It is not surprising that when he had access to a camera he made use of it enthusiastically. At the front from May 1916 on, he had photographed his fellow soldiers, sending the film back to Paris to be developed and arranging to get fresh rolls of film. Letters to his mother indicate that he planned to make an album of these wartime photos. On July 15, less than two weeks before he left the front for Paris, his mother had sent him some fresh rolls of film. But because of the heavy fighting in the Somme campaign during July, Cocteau would have had little opportunity to take photographs. Back in Paris with the rolls of film he had left over, he took two photographs of Satie and Valentine Gross and brought the camera and film with him to Montparnasse on August 12. He might have been inspired to take the photographs as part of his overwhelming preoccupation with launching Parade. He was working with Satie on Parade, was sharing his hopes for the ballet in letters to Gross; and was planning to ask Picasso to work on the sets and costumes with them. When he brought the camera to Montparnasse, he seized the opportunity of photographing not only Picasso but also the group of artists that he met at the Rotonde. While the focus is undoubtedly on Picasso--he appears in all but four of the photographs taken that day--Cocteau casually photographed the group as they moved around, greeted each other, laughed and joked, walked away from him, clowned for the camera, or merely sat at the cafe table. Earlier amateur photography tended to yield static, separate photographs of friends and family members that were, and definitely looked, posed for the occasion. Time stopped and the photograph was taken. Cocteau's series of spontaneous unposed snapshots of the people he admired in Montparnasse show the determination of this artist to use a new medium in a way that suited his spirited and mercurial personality. Cocteau introduced a new realism into amateur photography by systematically documenting his day with Picasso.

Saturday, August 12, 1916, was a warm, sunny day, with the temperature reaching 27 degrees Celsius. Jean Cocteau arrived at the Cafe de la Rotonde in Montparnasse from the Right Bank apartment he shared with his mother at 10 Rue d'Anjou between 12:30 and 12:45 for a lunch date with Picasso. He brought his mother's Kodak camera, which he called "our family camera."' He had one roll of film in the camera, on which he had taken two photographs a day or two earlier, and three rolls in his pocket.

During the war the Cafe de la Rotonde, located at the intersection of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail, was the cafe where artists, writers, and anarchists would meet. Its owner, Victor Libion, was large and dignified, with an oversized mustache; he moved around the cafe, serving customers, listening to their problems, giving them advice and often a little money. He let artists sit in the cafe for hours with only one 10-centime cup of coffee and looked the other way when they broke the ends off the long loaves in the bread basket. Picasso, whose studio on Rue Schoelcher was about 500 meters away from the Rotonde, spent a lot of time there after the death of his lover Eva Gouel in December 1915. Thus, the Rotonde would be a logical spot for the two men to meet.

It is not clear who initiated the lunch date, nor how the party was formed. However, Max Jacob, Henri-Pierre Roche, and Manuel Ortiz de Zarate, although very different personalities, were all friends of Picasso. Ortiz de Zarate was working for him as studio assistant this summer. Roche had been declared unfit for war in the trenches but was in uniform as secretary to General P. M. G. Malleterre, commanding general at the Invalides.

In the summer of 1916 Roche was an active participant in the life of the artists, composers, and collectors still in Paris. His diary shows that he heard the concerts at Rue Huyghens in April, lent paintings to the group exhibition at Mme. Germaine Bongard's dress shop in May, and attended all the events surrounding the Salon d'Antin in July. He was close to Paul Poiret, whose sister, Nicole Groult, was one of his lovers this summer. In particular Roche was taking the collector Jacques Doucet to artists' studios. On the first of August they visited Picasso's studio, where Doucet had, in Roche's words, "gotten excited over a little table [still life] that I like and over a little harlequin." Roche acted for Doucet in asking Picasso about them, and on August 3, Picasso wrote Roche: "I had never thought about selling the harlequins. I had done [them] only as a study and for myself. The other small painting, the cup, with a black frame is 1500 francs, and the other cubist harlequin 1500. As for the other harlequins, the one of which I am sending you a sketch is 3000 . . . [letter incomplete]."

The next day they went to Picasso's studio again. While Doucet talked to the "beautiful and still seductive" Spanish patron/admirer of Picasso, Eugenia Errazuriz, Roche negotiated with Picasso: "3,500 or 4000 for the two little pictures that were admired the other day? . . . To simplify things, we tossed for the 500 and Picasso won and it was 4,000."

Max Jacob still lived on Rue Gabrielle in Montmartre. Although he wrote to Apollinaire at the front that "I don't go to Montparnasse any more, where I sin in a revolting manner," Jacob in fact visited Picasso regularly and spent his evenings in Montparnasse till long after the Metro closed for the night. This made it necessary for him, he explained in a letter to Maurice Raynal, "to borrow beds from foreigners, (Swedes or Russians), which indirectly gives rise to unforeseen scandalous scenes."

Cocteau began to take photographs of the assembled group; Marie Wassilieff arrived a few minutes later. Since the beginning of the war she had been running a canteen for artists in her studio, located in an impasse off Avenue du Maine. It provided cheap meals, and the authorities considered it to be a private club and not subject to the curfew imposed on all bars and cafes. A Swedish artist remembered:

In one corner, behind a curtain, was the kitchen where the cook Aurelie made food for forty-five people with only a two-burner gas range and one alcohol burner. For sixty-five centimes, one got soup, meat, vegetable, and salad or dessert, everything of good quality and well prepared, coffee or tea; wine was ten centimes extra.

The place would be full again by ten o'clock. Whiskey and wine were available. Picasso and Matisse would drop in; also Modigliani, Zadkine, Kisling, and--when they were on leave--Braque, Derain, Leger, and Apollinaire. The hours of talk in ten languages would occasionally be interrupted for impromptu musical performances.

At one o'clock, the group that had gathered at the Rotonde crossed the boulevards to go to lunch at Picasso's and Apollinaire's favorite restaurant, Chez Baty, on the southeast corner of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail. The restaurant occupied the ground floor in an old building, with sawdust covering the tile floors and an unexploded shell from the fighting during the Commune of 1871 lodged in one wall. The owner, Pere Baty, concentrated on his wine cellar, so that the restaurant was favored more for its fine wine than for its food. Apollinaire, in praising Pere Baty's "well-kept cave," called him "the last expert on wines," and writer Andre Billy remembered that before the war they always went there after editorial meetings for Apollinaire's literary magazine, Les Soirees de Paris:

We often lacked the money to pay the printer, but we always had in hand the demilouis necessary to eat together at Chez Baty.... Those evenings a small room was reserved for us along Boulevard Raspail.... At Chez Baty a bottle of Chambertin cost seven francs, a small glass of fin Clos-Vougeot fifty-five centimes. I remember these prices not because they were so low, but on the contrary because they were so high. However, Baty was a strong honest businessman and a good guy."

Picasso and his friends finished lunch that day at 2:15. After lunch Roche left the group and later wrote in his diary: "Lunch with Picasso, Max Jacob, Mme. Wassilieff, and Jean Cocteau, whom I see for the first time, on the terrasse of Baty. The conversation too 'witty' and tires me out."

The group crossed the boulevards again and sat down for coffee on the terrasse of the Rotonde, where Moise Kisling and Picasso's current girlfriend, Paquerette, joined them. According to Andre Salmon, Paquerette was one of the most "precious" models for designer Paul Poiret and "showed off in Montparnasse the chef d'oeuvres of Avenue d'Antin." He describes an outfit that might be the one she was wearing that day: "green shoes, a rosewood-colored dress, and an indescribable hat."

The group left the Rotonde at 2:45, and Cocteau took more pictures of them on the street. Jacob, with his infectious imagination and wit, took the initiative and arranged a number of amusing scenes for the camera. Anyone on the street was appropriated for his scenes: the shoeshine boy by the Metro entrance and the vegetable seller with her cart of dilapidated produce.

After this, Marie Wassilieff left the group, probably to take care of preparations for the evening dinner at the canteen in her studio. Kisling and his dog Kouski disappeared from the group, while Modigliani and Andre Salmon joined them in front of the Rotonde around 3:30. If these two arrived together, they might have been at lunch at Rosalie's on Rue Campagne-Premiere, Modigliani's favorite restaurant, run by an Italian former model. Or if Modigliani had been painting at Kisling's studio at 3 Rue Joseph Bara, which he did frequently during that year, there would have been time for Kisling to return home and tell Modigliani, and Salmon who lived across the street, that the group was at the Rotonde. Modigliani had probably not seen Cocteau since he and Kisling had both painted Cocteau's portrait in Kisling's studio in late April.

The group walked slowly down Boulevard du Montparnasse toward the church of NotreDame-des-Champs. It is probable that Jacob and Ortiz, to both of whom a vision of Christ had appeared on the same day in 1909, wanted to go into the church, possibly to confession, since even Jacob's conversion to Catholicism the year before could not rid him of his homosexual longings, against which he somewhat disingenuously continued to cry out, "If heaven witnesses my regrets, heaven will pardon me for the pleasures which it knows are involuntary."

This was also the direction to the Metro station for the Nord-Sud line at Gare Montparnasse. From here Jacob could have returned to Montmartre and Cocteau to Rue d'Anjou.

In any case, just before four o'clock Jacob used the church steps to stage two scenes of himself and Ortiz begging for and giving alms. A third photograph shows Jacob about to enter the church.

The rest of the group must have waited for him to emerge, since it was half an hour later that Cocteau took the next photograph, the last of the day. In it the group is gathered around Jacob on the bench in front of the building next to the church that housed the Paris administrative headquarters for the P.T.T. (Poste Telephone Telegraphe). Max Jacob again had center stage.

The next day Cocteau wrote to Valentine Gross, with his Right Bank arrogance undiminished:

Nothing very very new except that Picasso takes me to the Rotonde. I never stay more than a moment, despite the flattering welcome by the circle (perhaps I should say the cube).... Too much cafe-sitting brings sterility. I have made films of Picasso and Mlle. Paquerette, and of the young people who don't know better than to judge the world according to Mme. Bongard. You will see the prints."

(C) 1997 Billy Kluver All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-262-11228-0

Copyright 1997 The New York Times Company.

σχόλια